- Information by Map Unit

- Information by Topic

- Documents in SoLo

Links to other related sites

- About SoLo

-

- Mission

- Disclaimer

- Authors (complete list)

Productivity of the forest plant community results from interactions of shoots and roots with the environment. One of the more important and least understood biotic zones of interaction is the soil immediately surrounding and influenced by roots, known as the rhizosphere. Microorganisms and processes in the rhizosphere profoundly influence plant growth through effects on uptake, storage, and cycling of nutrients, suppression of pathogens, and development of soil structure. Rhizosphere organisms are affected by and contribute to the successional dynamics of forest communities. Protecting the functional biodiversity of rhizosphere organisms through proper management practices is essential to maintaining ecosystem health and resiliency.

Today's forest management decisions integrate increasingly complex and changing social, economic, and ecological values. Foresters not only are concerned with the basic silvicultural goals of harvesting and regeneration but also seek to sustain long-term productivity of forest sites, protect non timber resources such as water and scenery, and maintain biodiversity. All this requires understanding of how forest ecosystems function. Today, forestry and forest sciences are shifting dramatically from basing decisions on how trees operate to a holistic integration of how all the parts of a forest work together, how they are linked and interdependent.

The study of soil biology also has shifted fundamentally. Over the last decade, research has shown the critical linkage of soil microorganisms to forest productivity and community dynamics. Ecosystem studies quantified the tremendous energy invested by trees in fine root production and organisms growing in the immediate vicinity of these roots, known as the rhizosphere. As much as 80 percent of the photosynthate of trees is used to support fine roots and associated microorganisms (Fogel and Hunt 1983; Vogt and others 1982). Laboratory and field studies have shown that roots of the same or dissimilar plants can be connected by commonly shared symbiotic root fungi, the mycorrhizal fungi; carbon (sugars) and other nutrients can actually flow between connected plants (Read and others 1985). Increasing attention has been focused on the food web dynamics of soil organisms, particularly their relations to the vitality of highly visible aboveground organisms (Ingham and others 1985). An increasingly sophisticated and knowledgeable public is becoming aware of these tight ecosystem linkages. Such heightened awareness and demand for sustaining total ecosystems requires that forest managers stay current on the latest developments in the many disciplines of forest research.

Our previous research has concentrated on mycorrhizal fungi of forest trees, with emphasis on selection of beneficial fungus strains for inoculation of nursery seedlings. We tried to enhance seedling survival and growth on hard-to-regenerate sites by tailoring root systems with fungi adapted to the planting site. In addition to successfully developing this technology (see Castellano and Molina 1989), we encountered ecological concepts relevant to managing forest sites and protecting soil organisms. We found, for example, that the tremendous biological diversity of mycorrhizal fungi represents a similarly wide range of physiological diversity providing a wide range of benefits to plants in diverse habitats. Different site disturbances and patterns of reforestation affect the survival potential of mycorrhizal fungus propagules in the soil. Enhancement of seedling performance by mycorrhizal inoculation was most successful on drought-stressed sites with low population levels of residual mycorrhizal fungi. Such findings allowed development of testable hypotheses on how forest practices degrade the soil biological community in ways requiring inoculation. Our major goal now is to achieve better understanding of the natural forest processes that maintain viable populations of soil microoganisms after natural disturbance and thus contribute to forest recovery; that is, natural soil biological mechanisms of resiliency (see Perry and others 1987).

The objectives of this paper are to (1) overview fundamental concepts in forest soil biology, including key organisms and processes; (2) discuss rhizosphere ecology in the context of interactions and interdependencies of aboveground and belowground biotic communities; (3) emphasize protection of the soil biological community through wise resource management; and (4) update forest managers on research directions in forest soil biology.

Productivity of plant communities results from interactions of shoots and roots with the environment. One of the more important and least understood biotic zones of interaction is the soil immediately surrounding and influenced by roots-the "rhizosphere." Depending on site quality, forests can divert 50 to 80 percent or more of the net carbon fixed by photosynthesis to belowground processes (Fogel and Hunt 1983; Vogt and others 1982). Although much goes to root growth, a relatively high proportion may be used to feed soil microorganisms and fuel processes in the rhizosphere. This is not energy lost from the plant. These organisms and processes in the rhizosphere influence plant growth positively by enhancing nutrient uptake, storage, and cycling, moisture storage, pathogen suppression, development of soil structure, and protection against environmental extremes. The specialized rhizosphere microorganisms include mycorrhizal fungi, saprophytes, microfauna, pathogens, and growth-promoting and deleterious bacteria (see Curl and Truelove 1986; Linderman 1986 for more detail).

Factors that influence rhizosphere organisms include the age and kinds of plant, soil physical conditions, temperature, moisture, interactions with other soil microbes, and cultural practices (Katznelson 1965). Rhizosphere activities fluctuate in response to changes in plant, microbial community, edaphic, and environmental factors.

Unfortunately, except for mycorrhizal fungi of forest trees and nitrogen fixation in forests, most of our knowledge of rhizosphere dynamics comes from agricultural soils and crop research. Forest soils and processes differ fundamentally from agricultural soils; we are just beginning to probe the complex interactions within the rhizospheres of forest plants and their impacts on forest health and productivity. The following sections discuss key rhizosphere organisms and processes and their importance at forest community and ecosystem levels.

Biological activity and function is not distributed homogeneously across the soil environment. Intense biological activity typically extends about 2 mm out from fine roots and differs significantly from that in the bulk soil in numbers, types, and functions of organisms. Fine roots maneuvering through the soil exude amino acids, carbohydrates, and other compounds that stimulate growth of bacteria, actinomycetes, and fungi. These, in turn, produce compounds that repel or stimulate other soil organisms. The microflora is a prime food for "grazer" herbivores such as mites, nematodes, and springtails, which, in turn, fall prey to carnivores such as centipedes and spiders. Saprophytes decay the dead remains of microbes and roots in the rhizosphere and decompose complex organic molecules into basic components. Nutrients and waste released through decomposition are captured and returned to the host plant via mycorrhizal fungi. The fine roots of forest plants and their associated mycorrhizal fungi form an often contiguous network in the upper soil profile. This rooting zone is essentially a rhizosphere zone in which the vast majority of soil nutrients are recycled and retained.

Rhizosphere organisms receive nutrients primarily from root exudates, and nonrhizosphere organisms use organic residues in varying stages of decomposition (Rambelli 1973). The different microbial compositions of bulk and rhizosphere soils reflect these nutritional modes. The rhizosphere microenvironment also differs strongly from that of the bulk soil. Organic substrates and compounds of all kinds are more abundant in the rhizosphere than in bulk soil. This includes humic compounds, polysaccharides, hormones, chelators, and enzymes (Perry and others 1987). The supply of other nutrients such as N, P, Mn, and Fe may limit plant growth because of intense utilization and competition (Foster 1988).

Rhizosphere organisms experience large fluctuations in pH as different ions are removed from the soil by roots and replaced by balancing ions. Similarly, rhizosphere organisms may experience very low water potentials as water is removed by high transpiration rates. High osmotic potential can also occur from the accumulation of calcium at the root surfaces. Local microaerophyllic or anaerobic conditions can develop in the rhizosphere due to high respiration rates by roots and microorganisms (Foster and Bowen 1982), further influencing microbial composition and processes. Rhizosphere organisms can also be buffered from unfavorable environmental changes by gels and polysaccharides secreted by roots and microorganisms.

Mycorrhiza literally means "fungus root" and represents the intimate association between the fine roots of plants and specialized symbiotic fungi. Readers are referred to recent reviews of the tremendous body of literature on this mutualistic symbiosis for greater detail (Castellano and Molina 1989; Harley and Smith 1983; Perry and others 1987). We emphasize mycorrhizae in this section and others because most land plants depend on mycorrhizae for nutrient uptake, and mycorrhizae perform far-reaching ecosystem functions in our forests.

Mycorrhizae come in several types and involve thousands of fungus species. Understanding the overall variety of mycorrhizal types, differences between groups of plants in their mycorrhizal association, and physiological and ecological differences among the fungi is key to understanding their biotic diversity and impact on ecosystem function and community development. Ectomycorrhizae, vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae (VAM), and ericaceous mycorrhizae prevail in temperate forests.

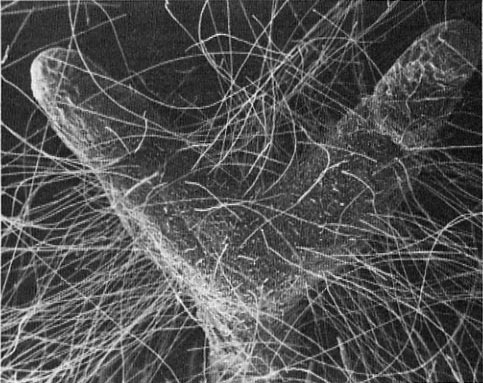

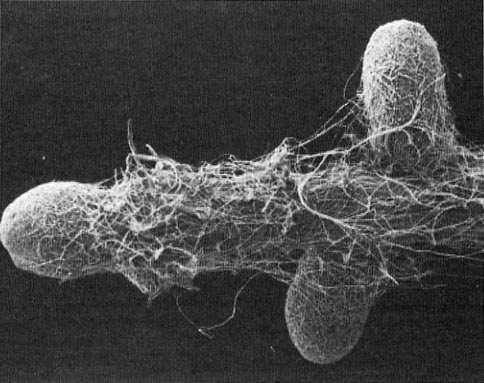

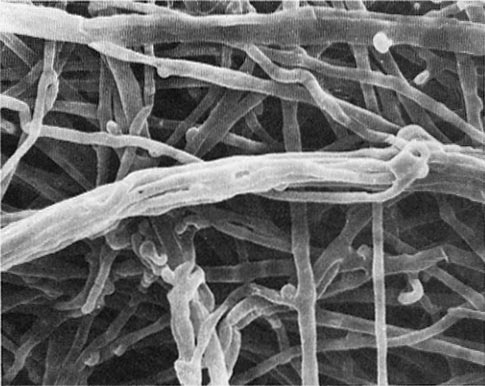

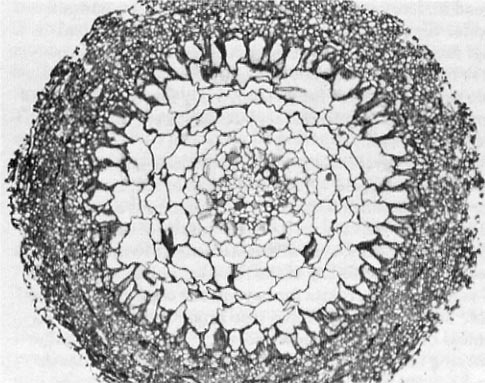

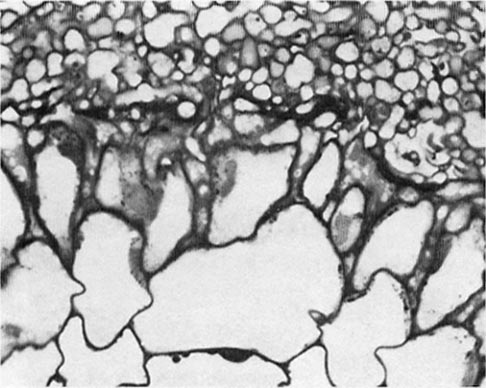

Ectomycorrhizae predominate in temperate forests of the Pacific Northwest because species of the Pinaceae, Betulaceae, and Fagaceae all form this type. Ectomycorrhi zal fungi form an often colorful sheath or mantle around feeder roots and penetrate the root cortex to form the "Hartig net," a zone of nutrient exchange between fungus and host (see figs. 1-5). These fungi also extensively colonize the soil, often to form visible, persistent mats in the upper soil and humus. Most fleshy mushrooms that fruit on the forest floor as well as the hidden subterranean truffles are fruiting bodies of the ectomycorrhizal fungus colonies in the soil. A walk through the woods during the mushroom season reveals the abundance and diversity of these fungi; thousands of ectomycorrhizal fungus species associate with trees in the Pacific Northwest.

Figure 1—Scanning electron micrograph of pine ectomycorrhiza showing the typically forked branching pattern. Note the numerous hyphae radiating out from the fungus mantle. (Magnification = 93x.) (Photo courtesy of Drs. H. B. Massicotte and R. L. Peterson, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada.)

Figure 2—Scanning electron micrograph of a eucalypt ectomycorrhiza showing a pinnate branching pattern and a well-developed mantle. (Magnification = 77x.) (Photo courtesy of Drs. H. B. Massicotte and R. L. Peterson, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada.)

Figure 3—Scanning electron micrograph of an ectomycorrhizal mantle showing the complex development of interwoven hyphal strands and individual hyphae. (Magnification = 1310x.) (Photo courtesy of Drs. H. B. Massicotte and R. L. Peterson, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada.)

Figure 4—Transverse section through an ectomycorrhiza of red alder. Note the well-developed fungal sheath or mantle. (Magnification = 154x.) (Photo courtesy of Drs. H. B. Massicotte and R. L. Peterson, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada.)

Figure 5—High-magnification transverse section of red alder ectomycorrhiza showing fungal penetration into the epidermis to form the Hartig net. (Magnification = 655x.) (Photo courtesy of Drs. H. B. Massicotte and R. L. Peterson, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada.)

The VAM are also widespread in our forests but have received less attention because they primarily occur on understory species and herbaceous plants. They are typical on cedars (Thuja, Chamaecyparis, and Libocedrus) and redwoods (Sequoia and Sequoiadendron), however. Unlike the ectomycorrhizal fungi, VAM fungi do not strikingly modify root morphology; they ramify in fine roots to form specialized structures (arbuscules and vesicles). Although they do not form the showy mycelia of the ectomycorrhizal fungi in the soil, they, too, extensively colonize the soil and bring in nutrients to the plants. The VAM fungi only number in the hundreds, and most can form mycorrhizae with a wide range of plant species.

Ericaceous mycorrhizae, as the name implies, are formed exclusively with members of the Ericales; for example, Gau ltheria, Rhododendron, and Vaccinium. Although this seems a narrow grouping, the Ericaceae are widespread understory components in coastal and mountain forests. Similarly to VAM, the ericaceous mycorrhizal fungi ramify through the fine, hairlike rootlets, to form dense hyphal coils but not to modify the root structure as do ectomycorrhizal fungi. Relatively few fungus species form this type of mycorrhizae, but they seem to be widespread in the soil.

Benefits of mycorrhizae to plants include enhanced uptake of nutrients and water, protection against pathogens, improved resistance to drought, enlarged root systems, and tolerance of heavy metal. The uptake of immobile ions such as phosphorus, typically benefiting growth of hosts, is mostly due to the ability of the fungus hyphae to explore a soil volume for nutrients far beyond the capabilities of the roots. Ectomycorrhizal fungi also produce hormones that promote branching of feeder roots, increasing not only the absorbing root surface but also the contact and exchange zone between fungus and plant. A recent study (Read 1987) also shows an important role for nitrogen uptake by mycorrhizal fungi, particularly from organic nitrogen sources. For example, ericaceous mycorrhizal fungi can degrade protein as well as other organic nitrogen sources (Read 1987). Such an ability may be critically important in organic substrates such as rotting logs or buried wood, common niches for ericaceous plants.

The plants pay for such benefits in photosynthate shuttled to roots. Indeed, mycorrhizal fungi are strongly dependent on a continuous supply of plant sugars and other organic compounds such as vitamins. The fungus functions as a structure of the root system supported by plant energy. The mycorrhizal fungi produce organic exudates and undergo rapid turnover, thereby attracting other microorganisms that feed in the hyphal zone. In essence then, mycorrhizae extend rhizosphere to a zone termed the "mycorrhizosphere" (Rambelli 1973).

Most plant benefits noted here were discovered in comparisons of mycorrhizal with nonmycorrhizal seedlings. We are only beginning to understand the role of mycorrhizal fungi and other rhizosphere organisms in forest community development and ecosystem function.

Nitrogen is typically the most limiting nutrient in Pacific Northwest forests. Natural inputs of nitrogen through the process of nitrogen gas fixation are essential to maintain long-term forest productivity in much of the Western United States.

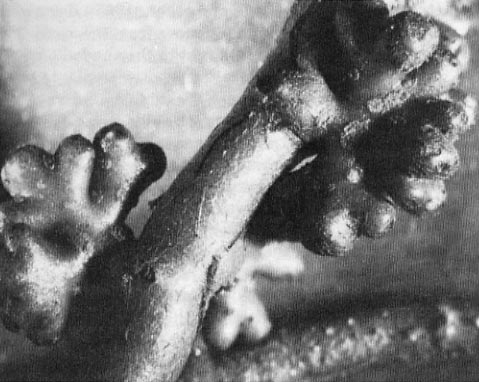

Symbiotic nitrogen fixation can add substantial nitrogen continuously to Pacific Northwest forests (Wollum and Youngberg 1964). Common nodulated plants such as lupine, alder, and snowbrush (Lupinus, Alnus, and Ceanothus) species form a mutually beneficial relationship with certain bacteria or actinomycetes that convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonium nitrogen (see fig. 6). This fixed nitrogen is released into the roots of host plants, thereby increasing nitrogen concentrations in living tissue (Tarrant and Trappe 1971). As nitrogen is returned to the soil by litterfall and washing of leaves by rain, other species benefit, such as commercially important conifer species.

Figure 6—Scanning electron micrograph of nitrogen-fixing nodules formed on Alnus sinuata roots. (Magnification = 7.7x.) (Photo courtesy of Drs. H. B. Massicotte and R. L. Peterson, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada.) [Text description of this figure]

"Free-living" nitrogen fixation by bacteria living in close association with roots and mycorrhizae was first suggested by Richards and Voigt (1964), and the phenomenon is now well established (Chartarpaul and Carlisle 1983; Dawson 1983; Florence and Cook 1984; Li and Hung 1987). Nitrogen-fixing bacteria were observed in close association with the mycorrhizosphere of Pinus radiata D. Don (Rambelli 1973). We have also found nitrogen-fixing bacteria to associate with ectomycorrhizae of forest trees in the Pacific Northwest (Li and Hung 1987). Bacteria in the genera Azotobacter, Azospirillum, and Clostridium fix nitrogen under conditions characteristic of the rhizosphere, where oxygen concentrations are low (Giller and Day 1985). The amount of rhizosphere nitrogen fixation differs by mycorrhiza type, host plant, and plant community. For example, Amaranthus and others (1989) found significantly higher nitrogenase activity in Douglas-fir rhizospheres associated with cleared areas of Arctostaphylos viscida shrubs compared to Douglas-fir grown in adjacent cleared areas of annual grass. Nitrogen is fixed by free-living bacteria in buried wood (Jurgensen and others 1984), an important niche for mycorrhizal development (Harvey and others 1987). Although the amount of nitrogen added to forest sites by free-living microoganisms is small compared to symbiotic sources, steady accretions especially in the immediate root zone can contribute significantly to the overall long-term nitrogen budget. Thus, silvicultural use of rhizosphere organisms to improve nitrogen levels deserves continuing research.

Many soil animals interact in the rhizosphere. Recent attention has been devoted to soil animals that influence nutrient cycling by acting as microbial grazers in the rhizosphere (Coleman and others 1984; Elliot and others 1980; Ingham and others 1985). Nematodes, protozoa, amoebae, and microarthopods graze on fungi and bacteria in the rhizosphere and release nitrogen in a form available to plants. Nutrient fluxes due to grazing can be significant. Persson (1983) estimated that 10 to 50 percent of total nitrogen mineralization in a Swedish pine forest is mediated by soil invertebrates. Louisier and Parkinson (1984) estimated that testate amoebae alone consume more than 13,000 kg/ha/yr in an aspen woodland soil; 85 percent of that consumption was released or respired. This would release from 25 to 50 kilograms of N/ha/yr from bacterial biomass, an amount roughly equivalent to the amount annually taken up by trees. Invertebrates, particularly arthropods, may also move fungi, bacteria, and other microbes from rhizosphere to rhizosphere.

The ecology of soil pathogens and pathogen protection by rhizosphere organisms is poorly understood in forest soils; most research has concentrated on the root rot fungi in the genera Phellinus, Armillaria, and Fomes, which infect and persist in large structural roots and stumps. Feeder root pathogens are less well known. Soil biologists hypothesize that a "healthy" forest soil supports populations of microorganisms that compete or otherwise antagonize fine-root pathogens. For example, common pathogens in tree nursery soils are rarely isolated from forest soils. This phenomenon of naturally "suppressive soil" is a subject of considerable research. Ectomycorrhizal fungi can protect trees against fine-root pathogens by (1) providing a physical barrier (fungal mantle) against penetration, (2) depriving root pathogens of carbohydrates, (3) secreting inhibitory antibiotic substances against pathogens, (4) promoting other rhizosphere organisms that inhibit pathogens, and (5) inducing biochemical changes in root cortical cells that inhibit pathogen infection and spread (Marx 1972; Zak 1964).

How do these mechanisms work in forest soils? In Australia, Malajczuk and McComb (1979) found significant differences between rhizosphere populations around mycorrhizal and nonmycorrhizal Eucalyptus seedlings in soils suppressive or conducive to the fungal pathogen Phytophthora cinnamoni Rands. High counts of bacteria were present throughout the fungal mantle within and between root cortical cells of mycorrhizal seedlings but were not present in nonmycorrhizal seedlings; in culture, many of the bacteria strongly antagonized root pathogens (Phytophthora and Pythium spp.). In the Pacific Northwest, Rose and others (1980) found that a free-living Streptomycete species from the rhizosphere of snowbrush (Ceanothus velutinus Dougl.) antagonized three common root pathogens: Phellinus weirii (Murr.) Gilb., Fomes annosus (Fries) Karst., and Phytophthora cinnamoni. In bareroot nurseries, the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria laccata (Scop.:Fr.) Berk. and Br. can reduce incidence of Fusarium root rot (Sinclair and others 1982). Nonmycorrhizal fungi can also inhibit pathogens. Common soil fungi in the genus Trichoderma can reduce the incidence of root rot in pine seedlings (Kelly 1976). Root-protecting organisms, such as symbionts and nitrogen fixers, are important components of "forest health." A research focus on the organisms involved and the effect of management practices on their survival and function is much needed.

An often-overlooked function of soil organisms is their dynamic contribution to soil structure, particularly aggregate formation and stability (Perry and others 1987). The resulting porosity, essential for movement of air and water required by roots and microorganisms, greatly influences forest productivity. Mycorrhizal fungi and other rhizosphere microbes influence soil structure by producing humic compounds (Tan and others 1978), accelerating the decomposition of primary minerals (Cromack and others 1979), and secreting organic "glues" called extracellular polysaccharides (Sutton and Shepard 1976; Tisdale and Oades 1979). Extracellular polysaccharides are especially efficient at stabilizing soil structure and act by linking mineral grains, homogenous clays, and humus into stable aggregates that maintain porosity (Toogood and Lynch 1959).

Because extracellular polysaccharides are also degraded by microbial activity, maintenance of soil structure depends on the relatively continuous flow of photosynthate into the rhizosphere. Without energy flowing from plants to rhizospheres, soil structure may be altered. Borchers and Perry (1989) found that the proportion of large aggregates was significantly reduced in two unreforested southern Oregon clearcuts. The management implications of this important soil biological function are clear: rapid tree regeneration or recolonization by pioneering vegetation are essential to supply soil organisms with the energy needed to maintain a functioning soil structure.

We typically consider the saprophytic microflora, the decomposers, as the primary soil organisms controlling nutrient cycling. Recent studies, however, show rhizosphere organisms also to be important in nutrient cycling, even though they receive energy primarily from root exudates; for example, ericaceous mycorrhizal fungi and ectomycorrhizal fungi can possess enzymes capable of degrading organic nitrogen into usable forms (Read 1987). Some ectomycorrhizal fungi can also degrade organic carbon sources, albeit at rates typically lower than saprophytic fungi. Under some circumstances, mycorrhizal fungi may compete with saprophytes to slow down overall rates of decomposition (Gadgil and Gadgil 1975). Other direct physiological mechanisms suggest further roles of mycorrhizal fungi in nutrient cycling. For example, ectomycorrhizal fungi release enzymes that increase the availability of phosphorus to higher plants (Alexander and Hardy 1981; Ho and Zak 1979; Williamson and Alexander 1975). This extraction process extends to other nutrients, especially immobile heavy metals, and enters them into the forest nutrient cycle. Many ectomycorrhizal fungi and rhizosphere bacteria produce chelating agents called siderophores that are especially important for iron uptake by plants (Graustein and others 1977; Perry and others 1982; Powell and others 1980). Still other fungi produce oxalic acid that enhances the primary weathering of soil particles (Cromack and others 1979).

Maintenance of forest productivity requires not only the steady cycling of nutrients but also the conservation of nutrient capital. The living microbial biomass in the rhizosphere is exceedingly large, especially when one considers the extensive mats of ectomycorrhizal fungi composed of rope like hyphal aggregations that tenaciously store nutrients. Thus, few nutrients leach out when populations of rhizosphere organisms are healthy and active. This is particularly important for soluble forms of nitrogen such as nitrate, which is susceptible to leaching. As a primary ecosystem function, rhizosphere organisms form a web to capture and assimilate nitrogen and other nutrients into complex organic compounds and then slowly release them into the forest ecosystem.

Several exciting directions of rhizosphere research emphasize that the successional dynamics of plant communities and rhizosphere microorganisms are intricately related and interdependent. Because tree harvest and site preparation set the stage for forest community succession, they likewise impact the belowground successional dynamics. We expect that major management implications on forest recovery will develop from soil biological investigations.

Most leads on rhizosphere-plant community dynamics deal primarily with mycorrhizal relationships, so we emphasize those here. Many different host species can form mycorrhizae with the same fungi. Laboratory studies indicate that plants connected by a shared fungus can exchange nutrients, including carbon and minerals, via the "hyphal bridge" (Read and others 1985); if one of the plants is shaded, carbon may move from the strongly photosynthesizing plant in full light to the shaded plant. The implication of this to interactions between plants and nutrient cycling is enormous. For example, understory plants or late successional plants may be able to receive carbon from overstory plants. Seedlings may survive in the shady understory due to overstory carbon support. But another more important mechanism likely occurs in these rhizosphere relationships between plants, a phenomenon termed rhizosphere "legacy" (see Perry and others 1987). A plant species entering in the later stages of succession can grow into a community of rhizosphere organisms that has been developed and maintained by earlier plant species. The later successional plants can utilize a fully functional rhizosphere community developed at the expense (that is, photosynthates) of early successional plant species. Such a functional rhizosphere connection in "successional time" is an important but poorly understood component of community development.

One should not suppose, however, that all plants are connected by mycorrhizal fungi or exchange nutrients through such fungi. Trees that form only ectomycorrhizae cannot associate with VA or ericaceous mycorrhizal fungi, and so plants that exclusively form these different types of mycorrhizae would not be directly linked. Also, several ectomycorrhizal fungi form mycorrhizae only with a particular genus of trees. For example, many fungus species are "host-specific" to Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) or the genus Pinus. The important point is that such a rich assemblage of rhizosphere organisms with different plant compatibilities enables the soil organisms to "partition" use of the soil by the plants. In essence then, when there is a variety of plants in a forest a related mosaic of belowground rhizosphere organisms partition the soil resource, at times influencing plant-plant interactions and at other times not. We believe that compatible and competitive interactions between plants as mediated by rhizosphere organisms contribute significantly to community development (Perry and others 1989).

One final concept of rhizosphere development is important to forest community succession. Studies in birch (Betula) stands in Great Britain reveal that certain mycorrhizal fungi dominate tree root systems of young birch trees, and other fungi are common in older stands (Mason and others 1987). Such fungi have been termed "early and late-stage" fungi, respectively. These two groups of fungi differ physiologically, with the late group generally better adapted to deal with soils high in organic matter. We are only beginning to evaluate such phenomena among mycorrhizal associations in Pacific Northwest forests, where tree and habitat diversity is greater than in Great Britain. We hypothesize, however, that the species composition of rhizosphere organisms shifts tremendously as forests mature, reflecting changes in soil characters as well as forest composition (Amaranthus and Perry 1987). Many ectomycorrhizal fungi show strong preference for specific soil microniches. For example, some fungus species predominate in highly organic substrates such as buried wood; others proliferate in exposed mineral soils. In addition to improving our knowledge on the dynamics of belowground biological succession, understanding such fundamentally different ecological strategies of mycorrhizal fungi and other rhizosphere microorganisms will allow us to maintain or, if necessary, reestablish viable populations of beneficial soil organisms on degraded sites.

Our studies in the Siskiyou Mountains of southwestern Oregon and northern California provide invaluable leads in testing community-level hypotheses of interactions between plants and soil organisms. Many of the pioneering hardwood shrubs and trees of these forests form mycorrhizae with the same fungi as do the timber tree species. Amaranthus and Perry (1989) show the lasting beneficial "legacy" effect of rhizosphere organisms in the soil beneath pioneering hardwoods. They hypothesize that the diverse plant species in these typically harsh forest habitats have evolved mutual compatibilities between rhizosphere organisms. This ensures not only rapid occupancy of the sites by pioneering plants but also maintenance of soil organisms that will benefit later successional stages. Such a legacy may also operate under the proposed system of green tree retention; the ramifications of such rhizosphere mechanisms may be important in other forest areas in the Pacific Northwest.

As we develop holistic approaches to understanding forest ecosystems and integrated, ecologically based management tools, we must factor in the inseparable connections to soil organisms. Just as forests invest tremendous capital in the form of photosynthates to fuel beneficial soil organisms, so too must we protect this unseen and overlooked ecosystem. We need to better understand its "functional biodiversity."

The number of species of microorganisms in the soil is far greater than aboveground plants and animals, but it is difficult to quantify. Also, although many soil organisms perform similar processes, reflecting a "redundancy in function," they may have different ecologies; for example, different functions during the year or over successional time. Our goal was to define and characterize viable population levels of critical functional groups in a diversity of forest types and age classes so that we can predict when forest systems are becoming degraded. Understanding how the functional biodiversity of the soil biota acts as a biological "buffer" to forest disturbance and contributes to recovery will be an area of intense investigation.

Other challenges involve linking soil biological science to the complex issues of long-term site productivity and vegetation shifts during rapid global climate change. Sharpened understanding of soil biology, particularly the tight linkages in the rhizosphere, is paramount to developing sound ecological guidelines to protect the living resource of the soil.

Alexander, I. J.; Hardy, K. 1981. Surface phosphatase activity of Sitka spruce mycorrhizas from a serpentine site. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 13: 301-305.

Amaranthus, M. P.; Perry, D. 1987. Effect of soil transfer on ectomycorrhizal formation and the survival and growth of conifer seedlings on old, nonreforested clear-cuts. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 17: 944-950.

Amaranthus, M. P.; Perry, D. 1989. Interaction effects of vegetation type and Pacific madrone soil inoculum on survival, growth, and mycorrhiza formation of Douglas-fir. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 19: 550-556.

Amaranthus, M. P.; Molina, R.; Trappe, J. 1989. Long-term forest productivity and the living soil. In: Perry, D. A.; Meurisse, R.; Thomas, B.; Miller, R.; Boyle, J.; Means, J.; Perry, C. R.; Powers, R. F., eds. Maintaining long-term productivity of Pacific Northwest ecosystems. Portland, OR: Timber Press: 36-52.

Borchers, J. G.; Perry, D. A. 1989. Organic matter content and aggregation of forest soils with different textures in southwest Oregon clearcuts. In: Perry, D. A.; Meurisse, R.; Thomas, B.; Miller, R.; Boyle, J.; Means, J.; Perry, C. R.; Powers, R. F., eds. Maintaining long-term productivity of Pacific Northwest ecosystems. Portland, OR: Timber Press: 245.

Castellano, M. A.; Molina, R. 1989. Mycorrhizae. In: Landis, T. D.; Tinus, R. W.; McDonald, S. E.; Barnett, J. P. The container tree nursery manual. Vol. 5. Agric. Handb. 674. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 101-167.

Chatarpaul, L.; Carlisle, A. 1983. Nitrogen fixation: a biotechnological opportunity for Canadian forestry. Forestry Chronicle. 59: 249-250.

Coleman, D. C.; Anderson, R. V.; Cole, C. V.; McClellan, J. F.; Woods, L. E.; Trofymow, J. A.; Elliot, E. T. 1984. Roles of protozoa and nematodes in nutrient cycling. In: Microbial-plant interactions. Madison, WI: Soil Science Society of America: 17-28.

Cromack, K.; Sollins, P.; Graustein, W. C.; Seidel, K.; Todd, A.; Spycher, W. G.; Ching, Y. L.; Todd, R. L. 1979. Calcium oxialate accumulation and soil weathering in mats of the hypogeous fungus Hysterangeum crassum. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 11: 463-468.

Curl, E. A.; Truelove, B. 1986. The rhizosphere. New York: Springer-Verlag. 288 p.

Dawson, J. O. 1983. Dinitrogen fixation in forest ecosystems. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 29: 979-992.

Elliot, E. T.; Anderson, R. V.; Coleman, D. D.; Cole, C. V. 1980. Habitable pore space and microbial trophic interactions. Oikos. 35: 327-335.

Florence, L. Z.; Cook, F. D. 1984. Asymbiotic N-fixing bacteria associated with three boreal conifers. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 14: 595-597.

Fogel, R.; Hunt, G. 1983. Contribution of mycorrhizae and soil fungi to nutrient cycling in a Douglas-fir ecosystem. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 13: 219-232.

Foster, R. C. 1988. Microenvironments of soil microorganisms. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 6: 189-203.

Foster, R. C.; Bowen, G. D. 1982. Plant surfaces and bacterial growth: the rhizosphere and rhizoplane. In: Mount, M. S.; Lacy, G. H., eds. Phytopathogenic prokaryotes. Vol. I. New York: Academic Press: 159-185.

Gadgil, R. L.; Gadgil, P. D. 1975. Suppression of litter decomposition by mycorrhizal roots of Pinus radiata. New Zealand Journal of Botany. 5: 33-41.

Giller, K. E.; Day, J. M. 1985. Nitrogen fixation in the rhizosphere: significance in natural and agricultural systems. In: Fitter, A. H.; Atkinson, D.; Read, D. J.; Usher, M. B., eds. Ecological interactions in soil. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications: 127-147.

Graustein, W.; Cromack, K., Jr.; Sollins, P. 1977. Calcium oxalate: occurrence in soils and effect on nutrient and geochemical cycles. Science. 198: 1252-1254.

Harley, J. L.; Smith, S. E. 1983. Mycorrhizal symbioses. London: Academic Press. 483 p.

Harvey, A. E.; Jurgensen, M. F.; Larsen, M. J.; Graham, R. T. 1987. Relationships among soil microsite, ectomycorrhizae, and natural conifer regeneration of old-growth forests in western Montana. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 17: 58-62.

Ho, I.; Zak, B. 1979. Acid phosphatase activity of six ectomycorrhizal fungi. Canadian Journal of Botany. 57: 1203-1205.

Ingham, R. E.; Trofymow, J. A.; Ingham, E. R.; Coleman, D. C. 1985. Interactions of bacteria, fungi and their nematode grazers: effects on nutrient cycling and plant growth. Ecological Monographs. 55: 119-140.

Jurgensen, M. F.; Larsen, M. J.; Spano, S. D.; Harvey, A. E.; Gale, M. R. 1984. Nitrogen fixation associated with increased wood decay in Douglas-fir residue. Forest Science. 30: 1038-1044.

Katznelson, H. 1965. Nature and importance of the rhizosphere. In: Baker, K. F.; Snyder, W. C., eds. Ecology of soil borne plant pathogens: prelude to biological control. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press: 187-209.

Kelly, W. D. 1976. Evaluation of Trichoderma harzianum integrated clay granules as a biocontrol for Phytophthora cinnamoni causing damping off of pine seedlings. Phytopathology. 66: 1023-1027.

Li, C. Y.; Hung, L. L. 1987. Nitrogen-fixing (acetylene-reducing) bacteria associated with ectomycorrhizae of Douglas-fir. Plant and Soil. 98: 425-428.

Linderman, R. G. 1986. Managing rhizosphere microorganisms in the production of horticultural crops. Hort Science. 21: 1299-1302.

Louisier, J. D.; Parkinson, D. 1984. Annual population dynamics and production ecology of Tesacea (Protozoa, Rhizophodo) in an aspen woodland soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 16: 103-114.

Malajczuk, N.; McComb, A. J. 1979. The microflora of unsuberized roots of Eucalyptus calophylla R. Br. and Eucalyptus marginata Donn. ex Sm. seedlings grown in soils suppressive and conducive to Phytophthora cinnamoni Rands. 1. Rhizoplane bacteria, actinomycetes and fungi. Australian Journal of Botany. 27: 235-272.

Marx, D. H. 1972. Ectomycorrhizae as biological deterrents to pathogenic root infections. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 10: 429-454.

Mason, P. A.; Last, F. T.; Wilson, J.; Deacon, L. V.; Fleming, L. V.; Fox, F. M. 1987. Fruiting and successions of ecto mycorrhizal fungi. In: Pegg, G. F.; Ayres, P. G., eds. Fungal infection of plants. Cambridge University Press: 253-268.

Perry, D. A.; Amaranthus, M. P.; Borchers, J. G.; Borchers, S. L.; Brainerd, R. E. 1989. Bootstrapping in ecosystems. Bioscience. 39: 230-237.

Perry, D. A.; Meyer, M. M.; Egeland, D.; Rose, S. L.; Pilz, D. 1982. Seedling growth and mycorrhizal formation in clearcut and adjacent undisturbed soils in Montana: a greenhouse bioassay. Forest Ecology and Management. 4: 261-273.

Perry, D. A.; Molina, R.; Amaranthus, M. P. 1987. Mycorrhizae, mycorrhizospheres, and reforestation: current knowledge and research needs. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 17: 929-940.

Persson, H. 1983. Influence of soil animals on nitrogen mineralization in a northern Scots pine forest. In: Lebrun, P.; Andre, H. M.; deMedts, A.; Gregoire-Wibo, C.; Wauthy, G., eds. New trends in soil biology. Dieu-Brichart, Louvain-La-Neuve: 117-126.

Powell, P. E.; Cline, G. R.; Reid, C. P. P.; Szaniszlo, P. J. 1980. Occurrence of hydroxamate siderophore iron chelators in soils. Nature. 287: 833-834.

Rambelli, A. 1973. The rhizosphere of mycorrhizae. In: Marks, A. C.; Kozlowski, T. T., eds. Ectomycorrhizae: their ecology and physiology. London: Academic Press: 229-249.

Read, D. J. 1987. In support of Frank's organic nitrogen theory. Angewandte Botanik. 61: 25-37.

Read, D. J.; Francis, R.; Finlay, R. D. 1985. Mycorrhizal mycelia and nutrient cycling in plant communities. In: Fitter, A. H.; Atkinson, D.; Read, D. J.; Usher, M. B., eds. Ecological interactions in soils. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications: 193-218.

Richards, B. N.; Voigt, G. N. 1964. Role of mycorrhizae in nitrogen fixation. Nature. 201: 310-311.

Rose, S. L.; Li, C. Y.; Steibus-Hutchins, A. 1980. A streptomycete antagonist to Phellinus weirii, Fomes annosus, and Phytophthora cinnamoni. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 26: 583-587.

Sinclair, W. A.; Sylvia, D. M.; Larsen, A. O. 1982. Disease suppression and growth promotion in Douglas-fir seedlings by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria laccata. Forest Science. 28: 191-201.

Sinclair, W. A.; Sylvia, D. M.; Larsen, A. O. 1982. Disease suppression and growth promotion in Douglas-fir seedlings by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria laccata. Forest Science. 28: 191-201.

Sutton, J. C.; Sheppard, B. R. 1976. Aggregation of sand dune soil by endomycorrhizal fungi. Canadian Journal of Botany. 54: 326-333.

Tan, K. H.; Sihanonth, P.; Todd, R. L. 1978. Formation of humic acid like compounds by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Pisolithus tinctorius. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 42: 906-908.

Tarrant, R. F.; Trappe, J. M. 1971. The role of alder in improving the forest environment. Plant and Soil, Special Volume: 335-348.

Tisdall, J. M.; Oades, J. M. 1979. Stabilization of soil aggregates by the root systems of ryegrass. Australian Journal of Soil Research. 17: 429-441.

Toogood, J. A.; Lynch, D. L. 1959. Effect of cropping systems and fertilizers on mean weight-diameter of aggregates on Breton plot soil. Canadian Journal of Soil Science. 83: 151-156.

Vogt, K. A.; Grier, C. C.; Meier, C. E. 1982. Mycorrhizal role in net primary production and nutrient cycling in Abies amabilis ecosystems in western Washington. Ecology. 63: 370-380.

Williamson, B.; Alexander, I. J. 1975. Acid phosphatase localized in the sheath of beech mycorrhiza. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 7: 195-198.

Wollum, A. G., II; Youngberg, C. T. 1964. The influence of nitrogen fixation by non-leguminous woody plants on the growth of pine seedlings. Journal of Forestry. 62: 316-321.

Zak, B. 1964. Role of mycorrhizae in root disease. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 2: 377-392.

Paper presented at the Symposium on Management and Productivity of Western-Montane Forest Soils, Boise, ID, April 10-12, 1990.

Randy Molina is Research Botanist, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Corvallis, OR 97331; Michael Amaranthus is Soil Scientist, Siskiyou National Forest, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Grants Pass, OR 97526.